T.s. Eliot Reads: the Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

| The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock | |

|---|---|

| by T. S. Eliot | |

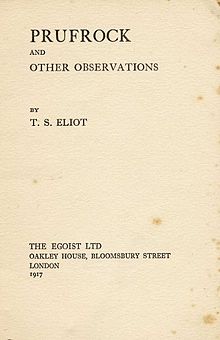

Encompass page of The Egoist, Ltd.'s publication of Prufrock and Other Observations (1917) | |

| Offset published in | June 1915 issue of Poetry [2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | magazine (1915): Harriet Monroe chapbook (1917): The Egoist, Ltd. (London)[1] |

| Lines | 140 |

| Pages | six (1915 printing)[2] eight (1917 printing)[ane] |

| Read online | The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock at Wikisource |

"The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock", commonly known every bit "Prufrock", is the beginning professionally published verse form past American-born British poet T. S. Eliot (1888–1965). Eliot began writing "Prufrock" in February 1910, and information technology was start published in the June 1915 effect of Poetry: A Mag of Verse [2] at the instigation of Ezra Pound (1885–1972). Information technology was later printed every bit part of a twelve-verse form pamphlet (or chapbook) titled Prufrock and Other Observations in 1917.[i] At the fourth dimension of its publication, Prufrock was considered outlandish,[3] but is now seen as heralding a paradigmatic cultural shift from late 19th-century Romantic verse and Georgian lyrics to Modernism.

The poem's structure was heavily influenced by Eliot'south all-encompassing reading of Dante Alighieri[4] and makes several references to the Bible and other literary works—including William Shakespeare's plays Henry 4 Part II, 12th Night, and Hamlet, the poetry of seventeenth-century metaphysical poet Andrew Marvell, and the nineteenth-century French Symbolists. Eliot narrates the experience of Prufrock using the stream of consciousness technique developed by his fellow Modernist writers. The poem, described equally a "drama of literary anguish", is a dramatic interior monologue of an urban man, stricken with feelings of isolation and an incapability for decisive action that is said "to epitomize frustration and impotence of the mod individual" and "correspond thwarted desires and modern disillusionment".[v]

Prufrock laments his physical and intellectual inertia, the lost opportunities in his life and lack of spiritual progress, and is haunted by reminders of unattained carnal love. With visceral feelings of weariness, regret, embarrassment, longing, emasculation, sexual frustration, a sense of disuse, and an awareness of mortality, "Prufrock" has become one of the most recognized voices in modern literature.[6]

Limerick and publication history [edit]

Writing and offset publication [edit]

Eliot wrote "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" between February 1910 and July or August 1911. Soon subsequently arriving in England to nourish Merton Higher, Oxford, Eliot was introduced to American expatriate poet Ezra Pound, who instantly deemed Eliot "worth watching" and aided the start of Eliot's career. Pound served as the overseas editor of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse and recommended to the mag'southward founder, Harriet Monroe, that Poetry publish "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock", extolling that Eliot and his work embodied a new and unique miracle amongst contemporary writers. Pound claimed that Eliot "has actually trained himself AND modernized himself ON HIS OWN. The remainder of the promising young have done one or the other, but never both."[seven] The poem was start published by the mag in its June 1915 issue.[2] [eight]

In Nov 1915 "The Dear Song of J. Alfred Prufrock"—forth with Eliot'southward poems "Portrait of a Lady", "The Boston Evening Transcript", "Hysteria", and "Miss Helen Slingsby"—was included in Catholic Anthology 1914–1915 edited by Ezra Pound and printed by Elkin Mathews in London.[ix] : 297 In June 1917 The Egoist, a small publishing house run past Dora Marsden, published a pamphlet entitled Prufrock and Other Observations (London), containing 12 poems by Eliot. "The Beloved Vocal of J. Alfred Prufrock" was the first in the volume.[1] Eliot was appointed banana editor of the Egoist in June 1917.[ix] : 290

Prufrock'due south Pervigilium [edit]

Co-ordinate to Eliot biographer Lyndall Gordon, when Eliot was writing the get-go drafts of "Prufrock" in his notebook in 1910–1911, he intentionally kept four pages bare in the center section of the poem.[x] According to the notebooks, now in the collection of the New York Public Library, Eliot finished the poem, which was originally published sometime in July and August 1911, when he was 22 years quondam.[11] In 1912, Eliot revised the poem and included a 38-line section now called "Prufrock's Pervigilium" which was inserted on those blank pages, and intended every bit a centre department for the poem.[10] However, Eliot removed this section shortly afterwards seeking the advice of his boyfriend Harvard acquaintance and poet Conrad Aiken.[12] This section would non be included in the original publication of Eliot's verse form merely was included when published posthumously in the 1996 drove of Eliot'southward early on, unpublished drafts in Inventions of the March Hare: Poems 1909–1917.[11] This Pervigilium section describes the "vigil" of Prufrock through an evening and night[eleven] : 41, 43–44, 176–90 described by i reviewer as an "erotic foray into the narrow streets of a social and emotional underworld" that portray "in damp particular Prufrock'south tramping 'through certain half-deserted streets' and the context of his 'muttering retreats / Of restless nights in i-dark cheap hotels.'"[13]

Critical reception [edit]

An unsigned review in The Times Literary Supplement on 21 June 1917 dismissed the poem, finding that "the fact that these things occurred to the mind of Mr. Eliot is surely of the very smallest importance to anyone, fifty-fifty to himself. They certainly have no relation to poetry."[xiv] [15]

The Harvard Vocarium at Harvard College recorded Eliot's reading of Prufrock and other poems in 1947, equally part of its ongoing series of poetry readings by its authors.[16]

Description [edit]

Championship [edit]

In his early drafts, Eliot gave the poem the subtitle "Prufrock amongst the Women."[11] : 41 This subtitle was plainly discarded before publication. Eliot called the poem a "honey vocal" in reference to Rudyard Kipling'due south verse form "The Love Vocal of Har Dyal", first published in Kipling's collection Patently Tales from the Hills (1888).[17] In 1959, Eliot addressed a meeting of the Kipling Club and discussed the influence of Kipling upon his own poetry:

Traces of Kipling announced in my own mature poetry where no diligent scholarly sleuth has notwithstanding observed them, merely which I am myself prepared to disclose. I once wrote a verse form chosen "The Love Vocal of J. Alfred Prufrock": I am convinced that it would never have been called "Honey Song" simply for a title of Kipling's that stuck obstinately in my caput: "The Dear Song of Har Dyal".[17]

Notwithstanding, the origin of the name Prufrock is not certain, and Eliot never remarked on its origin other than to merits he was unsure of how he came upon the name. Many scholars and indeed Eliot himself have pointed towards the autobiographical elements in the character of Prufrock, and Eliot at the fourth dimension of writing the poem was in the habit of rendering his proper name every bit "T. Stearns Eliot", very similar in form to that of J. Alfred Prufrock.[18] It is suggested that the name "Prufrock" came from Eliot's youth in St. Louis, Missouri, where the Prufrock-Litton Visitor, a large furniture store, occupied one city block downtown at 420–422 North Fourth Street.[19] [20] [21] In a 1950 letter, Eliot said: "I did not take, at the time of writing the poem, and take not all the same recovered, whatsoever recollection of having acquired this name in any manner, but I think that it must be assumed that I did, and that the memory has been obliterated."[22]

Epigraph [edit]

The draft version of the poem'southward epigraph comes from Dante'southward Purgatorio (XXVI, 147–148):[xi] : 39, 41

| 'sovegna vos a temps de ma dolor'. | 'exist mindful in due time of my pain'. |

He finally decided non to use this, but eventually used the quotation in the closing lines of his 1922 poem The Waste product Country. The quotation that Eliot did choose comes from Dante also. Inferno (XXVII, 61–66) reads:

| Due south'io credesse che mia risposta fosse | If I just thought that my response were fabricated |

In context, the epigraph refers to a meeting between Dante Alighieri and Guido da Montefeltro, who was condemned to the eighth circle of Hell for providing counsel to Pope Boniface VIII, who wished to apply Guido's advice for a nefarious undertaking. This encounter follows Dante's meeting with Ulysses, who himself is also condemned to the circle of the Fraudulent. According to Ron Banerjee, the epigraph serves to cast ironic light on Prufrock's intent. Like Guido, Prufrock had never intended his story to be told, and so by quoting Guido, Eliot reveals his view of Prufrock's love song.[25]

Frederick Locke contends that Prufrock himself is suffering from a separate personality of sorts, and that he embodies both Guido and Dante in the Inferno analogy. One is the storyteller; the other the listener who later on reveals the story to the earth. He posits, alternatively, that the role of Guido in the analogy is indeed filled by Prufrock, but that the part of Dante is filled by the reader ("Let usa go then, you and I"). In that, the reader is granted the power to do as he pleases with Prufrock'due south love song.[26]

Themes and interpretation [edit]

Because the poem is concerned primarily with the irregular musings of the narrator, it tin can exist difficult to translate. Laurence Perrine wrote, "[the verse form] presents the obviously random thoughts going through a person's head within a certain fourth dimension interval, in which the transitional links are psychological rather than logical".[27] This stylistic choice makes it difficult to determine exactly what is literal and what is symbolic. On the surface, "The Honey Vocal of J. Alfred Prufrock" relays the thoughts of a sexually frustrated middle-anile man who wants to say something only is afraid to do so, and ultimately does not.[27] [28] The dispute, however, lies in to whom Prufrock is speaking, whether he is actually going anywhere, what he wants to say, and to what the various images refer.

The intended audition is not evident. Some believe that Prufrock is talking to another person[29] or straight to the reader,[30] while others believe Prufrock's monologue is internal. Perrine writes "The 'yous and I' of the first line are divided parts of Prufrock'southward own nature",[27] while professor emerita of English language Mutlu Konuk Blasing suggests that the "you and I" refers to the relationship betwixt the dilemmas of the character and the author.[31] Similarly, critics dispute whether Prufrock is going somewhere during the course of the poem. In the first half of the poem, Prufrock uses various outdoor images (the sky, streets, cheap restaurants and hotels, fog), and talks virtually how there will be time for various things before "the taking of a toast and tea", and "time to plow back and descend the stair." This has led many to believe that Prufrock is on his mode to an afternoon tea, where he is preparing to enquire this "overwhelming question".[27] Others, however, believe that Prufrock is not physically going anywhere, only rather, is playing through it in his listen.[30] [31]

Possibly the nearly significant dispute lies over the "overwhelming question" that Prufrock is trying to inquire. Many believe that Prufrock is trying to tell a woman of his romantic involvement in her,[27] pointing to the various images of women'due south arms and clothing and the final few lines in which Prufrock laments that the mermaids will not sing to him. Others, however, believe that Prufrock is trying to express some deeper philosophical insight or disillusionment with guild, only fears rejection, pointing to statements that limited a disillusionment with society, such as "I have measured out my life with coffee spoons" (line 51). Many believe that the poem is a criticism of Edwardian order and Prufrock's dilemma represents the disability to alive a meaningful existence in the modern world.[32] McCoy and Harlan wrote "For many readers in the 1920s, Prufrock seemed to epitomize the frustration and impotence of the modern individual. He seemed to represent thwarted desires and modern disillusionment."[xxx]

In general, Eliot uses imagery which is indicative of Prufrock'southward character,[27] representing crumbling and decay. For example, "When the evening is spread out confronting the sky / Like a patient etherized upon a tabular array" (lines 2–3), the "sawdust restaurants" and "cheap hotels", the yellowish fog, and the afternoon "Asleep...tired... or it malingers" (line 77), are reminiscent of sluggishness and decay, while Prufrock's various concerns about his hair and teeth, as well every bit the mermaids "Combing the white hair of the waves diddled dorsum / When the wind blows the water white and black," show his business organization over aging.

Use of allusion [edit]

Similar many of Eliot's poems, "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" makes numerous allusions to other works, which are often symbolic themselves.

- In "Fourth dimension for all the works and days of easily" (29) the phrase 'works and days' is the title of a long poem – a description of agricultural life and a call to toil – past the early Greek poet Hesiod.[27]

- "I know the voices dying with a dying fall" (52) echoes Orsino'south start lines in William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night.[27]

- The prophet of "Though I have seen my head (grown slightly bald) brought in upon a platter / I am no prophet — and hither's no groovy matter" (81–2) is John the Baptist, whose caput was delivered to Salome by Herod as a reward for her dancing (Matthew 14:1–11, and Oscar Wilde's play Salome).[27]

- "To have squeezed the universe into a ball" (92) and "indeed there will exist time" (23) repeat the closing lines of Marvell'due south 'To His Coy Mistress'. Other phrases such equally, "there will be time" and "there is time" are reminiscent of the opening line of that poem: "Had we only earth enough and time".[27]

- "'I am Lazarus, come from the expressionless'" (94) may be either the beggar Lazarus (of Luke sixteen) returning for the rich homo who was non permitted to return from the dead to warn the brothers of a rich man virtually Hell, or the Lazarus (of John xi) whom Jesus Christ raised from the dead, or both.[27]

- "Full of high sentence" (117) echoes Geoffrey Chaucer's clarification of the Clerk of Oxford in the Full general Prologue to The Canterbury Tales.[27]

- "There will exist time to murder and create" is a biblical allusion to Ecclesiastes 3.[27]

- In the final section of the verse form, Prufrock rejects the thought that he is Prince Village, suggesting that he is merely "an bellboy lord" (112) whose purpose is to "advise the prince" (114), a likely allusion to Polonius — Polonius existence also "almost, at times, the Fool."

- "Amid some talk of you and me" may be[33] a reference to Quatrain 32 of Edward FitzGerald's translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam ("There was a Door to which I institute no Cardinal / There was a Veil past which I could not meet / Some little Talk awhile of Me and Thee / There seemed — and and then no more than of Thee and Me.")

- "I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each" has been suggested transiently to be a poetic allusion to John Donne's "Song: Go and grab a meteor" or Gérard de Nerval's "El Desdichado", and this discussion used to illustrate and explore the intentional fallacy and the place of poet's intention in critical inquiry.[34]

See likewise [edit]

- "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" in popular culture

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d Eliot, T. S. Prufrock and Other Observations (London: The Egoist, Ltd., 1917), 9–16.

- ^ a b c d Eliot, T. Due south. "The Dearest Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" in Monroe, Harriet (editor), Poetry: A Magazine of Poesy (June 1915), 130–135.

- ^ Eliot, T. South. (21 Dec 2010). The Waste Land and Other Poems. Broadview Press. p. 133. ISBN978-1-77048-267-eight . Retrieved 9 July 2017. (citing an unsigned review in Literary Review. v July 1917, vol. lxxxiii, 107.)

- ^ Hollahan, Eugene (March 1970). "A Structural Dantean Parallel in Eliot's 'The Beloved Song of J. Alfred Prufrock'". American Literature. ane. 42 (i): 91–93. doi:ten.2307/2924384. ISSN 0002-9831. JSTOR 2924384.

- ^ McCoy, Kathleen; Harlan, Judith (1992). English Literature From 1785. London, England: HarperCollins. pp. 265–66. ISBN006467150X.

- ^ Bercovitch, Sacvan (2003). The Cambridge History of American Literature. Vol. 5. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Academy Printing. p. 99. ISBN0521497310.

- ^ Mertens, Richard (August 2001). "Letter By Letter". The University of Chicago Magazine . Retrieved 23 Apr 2007.

- ^ Southam, B.C. (1994). A Guide to the Selected Poems of T.South. Eliot. New York Metropolis: Harcourt, Brace & Company. p. 45. ISBN057117082X.

- ^ a b Miller, James Edward (2005). T. S. Eliot: The Making of an American poet, 1888–1922. Academy Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 297–299. ISBN0271026812.

- ^ a b Gordon, Lyndell (1988). Eliot's New Life. Oxford, England: Oxford University Printing. p. 45. ISBN9780198117278.

- ^ a b c d due east Eliot, T. S. (1996). Ricks, Christopher B. (ed.). Inventions of the March Hare: Poems 1909–1917. New York City: Harcourt, Brace, and World. ISBN9780544363878.

- ^ Mayer, Nicholas B. (2011). "Catalyzing Prufrock". Journal of Mod Literature. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana Academy Press. 34 (iii): 182–198. doi:10.2979/jmodelite.34.3.182. JSTOR 10.2979/jmodelite.34.3.182. S2CID 201760537.

- ^ Jenkins, Nicholas (20 April 1997). "More American Than Nosotros Knew: Nerves, exhaustion and madness were at the core of Eliot'south early imaginative thinking". The New York Times . Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ Waugh, Arthur (October 1916). "The New Poesy". Quarterly Review (805): 299.

- ^ Wagner, Erica (four September 2001). "An eruption of fury". The Guardian.

- ^ Woodberry Poesy Room (Harvard College Library). Poetry Readings: Guide

- ^ a b Eliot, T.S. (March 1959). "The Unfading Genius of Rudyard Kipling". Kipling Periodical: nine.

- ^ Eliot, T. South. The Letters of T. S. Eliot. (New York: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich, 1988). one:135.

- ^ Montesi, Al; Deposki, Richard (2001). Downtown St. Louis. Mount Pleasant, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 65. ISBN0-7385-0816-0.

- ^ Christine H. The Daily Postcard: Prufrock-Litton – St. Louis, Missouri. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ Missouri History Museum. Lighting fixture in front of Prufrock-Litton Furniture Visitor. Retrieved xi June 2013.

- ^ Stepanchev, Stephen (June 1951). "The Origin of J. Alfred Prufrock". Modernistic Linguistic communication Notes. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University. 66: 400–401. JSTOR 2909497.

- ^ Eliot provided this translation in his essay "Dante" (1929).

- ^ Alighieri, Dante (1320). Divine Comedy. Translated by Hollander, Robert; Hollander, Jean. Princeton, New Bailiwick of jersey: Princeton Dante Projection.

- ^ Banerjee, Ron D. K. "The Dantean Overview: The Epigraph to 'Prufrock'" in Comparative Literature. (1972) 87:962–966. JSTOR 2907793

- ^ Locke, Frederick W. (Jan 1963). "Dante and T. S. Eliot's Prufrock". Modern Language Notes. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins Academy. 78: 51–59. JSTOR 3042942.

- ^ a b c d due east f thousand h i j k l m Perrine, Laurence (1993) [1956]. Literature: Structure, Audio, and Sense. New York City: Harcourt, Brace & Globe. p. 798. ISBN978-0035510705.

- ^ "On 'The Dearest Vocal of J. Alfred Prufrock' ", Modernistic American Verse, University of Illinois (accessed twenty April 2019).

- ^ Headings, Philip R. T. S. Eliot. (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1982), 24–25.

- ^ a b c Hecimovich, Gred A (editor). English 151-3; T. Southward. Eliot "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" notes (accessed 14 June 2006), from McCoy, Kathleen; Harlan, Judith. English Literature from 1785. (New York: HarperCollins, 1992).

- ^ a b Blasing, Mutlu Konuk (1987). "On 'The Love Vocal of J. Alfred Prufrock'". American Poetry: The Rhetoric of Its Forms. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN0300037937.

- ^ Mitchell, Roger (1991). "On 'The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock'". In Myers, Jack; Wojahan, David (eds.). A Profile of Twentieth-Century American Poetry. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois Academy Press. ISBN0809313480.

- ^ Schimanski, Johan Annotasjoner til T. S. Eliot, "The Dear Vocal of J. Alfred Prufock" (at Universitetet i Tromsø). Retrieved 8 August 2006.

- ^ Wimsatt, W. K., Jr.; Beardsley, Monroe C. (1954). "The Intentional Fallacy". The Verbal Icon: Studies in the Significant of Poesy. Lexington, Kentucky: University of Kentucky Press. ISBN978-0813101118.

Further reading [edit]

- Drew, Elizabeth. T. S. Eliot: The Design of His Poetry (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1949).

- Gallup, Donald. T. S. Eliot: A Bibliography (A Revised and Extended Edition) (New York: Harcourt Caryatid & Globe, 1969), 23, 196.

- Luthy, Melvin J. "The Case of Prufrock's Grammar" in College English (1978) 39:841–853. JSTOR 375710.

- Soles, Derek. "The Prufrock Makeover" in The English Journal (1999), 88:59–61. JSTOR 822420.

- Sorum, Eve. "Masochistic Modernisms: A Reading of Eliot and Woolf." Journal of Modern Literature. 28 (iii), (Spring 2005) 25–43. doi:10.1353/jml.2005.0044.

- Sinha, Arun Kumar and Vikram, Kumar. "'The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock' (Critical Essay with Detailed Annotations)" in T. South. Eliot: An Intensive Study of Selected Poems (New Delhi: Spectrum Books Pvt. Ltd, 2005).

- Walcutt, Charles Child. "Eliot's 'The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock'" in College English language (1957) 19:71–72. JSTOR 372706.

External links [edit]

- An passenger vehicle drove of T. S. Eliot's verse at Standard Ebooks

- Original text from Poetry mag June 1915

- Text and extended audio discussion of the poem

- The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock at the British Library

- Prufrock and Other Observations at Project Gutenberg

- Annotated hypertext version of the poem

-

Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Love_Song_of_J._Alfred_Prufrock

0 Response to "T.s. Eliot Reads: the Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock"

إرسال تعليق